Show and Tell: The Aspirational Travel Photograph

A newsletter on images and how they shape culture

A couple of years ago, there was a particular kind of image that you saw everywhere. It was usually a wide-angle shot of a travel destination. The space would be photographed in bright light, and all the colours would be tweaked to pop, more so than they ever do in real life. It would be populated by one or at most two human figures, seemingly rapt in the beauty around them. The photo would be accompanied by an unattributed quote. Something like “Collect moments, not things” or “Travel is the only thing that makes you richer”.

The goal of each person’s photograph seemed to be to tell others to go there. You, too - they seemed to say - must travel, because if you didn’t, your life would be too poor to bear thinking about. “To travel is to live” is another popular one.

The images rolled past us in the endless scroll, and inspired a peculiar kind of wanderlust. Isn’t wanderlust a lovely word? Thomas Aquinas said that lust was a sin. But wanderlust? Why, that sounds like stardust.

The value of a photograph

A travel photograph is an image of you in a place where you don’t belong. While you are a tourist, you are an observer and not a participant. The novelty of being in a different place and surrounded by a different culture is thrilling. Everything is fascinating: street signs, supermarkets, even other people’s routines. Playing tourist is engaging because you realise that humans are remarkably similar everywhere in the world, but also that it is the little differences between us that make life interesting and shape cultures. These are ideas well worth documenting and sharing.

Then there is my favourite part of travel: coming home. GK Chesterton remarked, “The whole object of travel is not to set foot on foreign land; it is at last to set foot on one’s own country as a foreign land.” Travel does change us, ever so slightly. Our routines feel different because we are different, changed by all we have seen.

I think Anthony Bourdain captured the attraction of travel well when he described it as “the gorgeous feeling of teetering in the unknown.” Now, I don’t wish to be prescriptive. People love to travel for a variety of reasons and I certainly don’t want them to feel censured by this newsletter. I know sometimes Bourdain’s quotes (and those by others like him) made me feel like my ambivalence about travel meant I wasn’t living a full or rich life, so I don’t care to do the reverse. People often give me that old chestnut about how you get stuck in a comfort zone, but hey, I unabashedly like comfort and routine. What I’m attempting to do here is to break down the marketing ideas around travel, as embodied by the aspirational travel photograph, to try and examine just how much of this wanderlust is a construction, and why.

Moments, not things

Two years ago, when we didn’t have pandemic restrictions or a war in Europe driving up oil prices, travel was easier than ever before in human history. As travel to ever more exotic locales opened up, we began flocking to them on saved up vacation days, and the trips we took were what we talked about when we were back with everyone we knew, whether they liked it or not. But really, this is a thing human beings have always done. Ibn Battuta did it to great effect back in the fourteenth century. Don’t tell me there weren’t some people in his acquaintance who ducked into alleys when they saw him coming, lest he bore them with an account of the wonders of Delhi one more time. That’s probably why he dictated the Rihla.

The Grand Tour of the eighteen hundreds was a rite of passage for every wealthy young Englishman. He was supposed to go, see Europe, and acquire polish, before settling down to a staid life of landowning and domesticity, occasionally regaling his acquaintances with off-colour stories from his Tour. Nowadays, we go on backpacking trips and settle down to home-ownership, and post our pictures on Instagram. What doesn’t get talked about enough is that travelling was expensive, and it still is a rich people pursuit. It is estimated that somewhere between just 2-4% of the world’s population takes international flights. In the buddy movie Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara, three childhood friends go to Spain to try out adventure sports and confront their demons. This is parodied hilariously by the stand-up comic Abhishek Upmanyu:

(A rough translation: Zoya Akhtar (the movie’s director) was making the point that you don’t get another life, and so you need to live and enjoy this one. So we asked, “How do we do that?” and Akhtar’s reply was, “Why, go to Spain. Go with your friends to Spain, stay in hotels, party, play in the La Tomatina festival.” We said, “We don’t have that much money.”

“Ah, buzz off then.” )

There is a certain unearned moral superiority at play in many of these travel images and captions: It is deemed vulgar to speak of money, but travel really is a form of consumption, and the aspirational travel photograph makes it increasingly conspicuous consumption. Yes, travel can open minds, but it isn’t the only thing that does. For instance, reading a book is considerably cheaper and can be just as educational. For that matter, books also lend themselves as props for similarly aspirational photographs. Travel seems a particularly expensive way of broadening one’s horizons, which is perhaps the point: the aspirational travel photographs show that you consume moments, not things. Expensive moments, in place of expensive things.

Whatever authentic means

Photographs have always been staged, but the staging used to once be the point. Think of the Victorian era photographs in which the subjects had to hold still for several minutes as mercury amalgamated with silver to form a daguerreotype of their image. The subjects would wait, still and unsmiling, in studied postures and carefully chosen clothes, for as long as it took for their images to form. Now, the whole purpose of staging is to make the photograph seem unstaged, or in millennial speak: authentic, which is one of those words with a slippery meaning. Authentic to what exactly? The place? Or the photographer’s vision of the place? To how the subject wishes to be seen? Or the marketer’s demand of how the place is to be portrayed?

We create images as stand-ins for experiences and control the staging of those images in many ways. Appearing to be alone in a crowded place. Pretending to read a book. Ignoring the camera. Contorting our bodies to make them appear more lithe, more tanned, closer to a constantly shifting “ideal”. We used to do this in portrait paintings, of course. Photography is simply faster. The same elite create the images that the rest mimic, in a culture where pretence is rewarded. Appearing to live a charmed life becomes the same thing as living a charmed life.

[Publicity] proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, or our lives, by buying something more. This more, it proposes, will make us in some way richer - even though we will be poorer by having spent our money.

Publicity persuades us of such a transformation by showing us people who have apparently been transformed and are, as a result, enviable. The state of being envied is what constitutes glamour. And publicity is the process of manufacturing glamour.

- John Berger

I wonder if this shift, from deliberately staged to staged-to-appear-unstaged occurred at around the same time as the emergence of “creators”. These are people who are both the subject of the photograph and the photographer, or the directors of the photograph. In that sense, they are the portrait subject and painter, filling canvas after canvas until they are satisfied with how they are portrayed. And in the aspirational travel photograph, they are also bending the place they are photographing to fit their idea of what their surroundings should be. Or, if they are successful, they are following a marketing brief because the image is being paid for as material for publicity. The rest of us consume these images and conflate the setting with the creator and long to go to this place that does not quite exist in the same form in any real sense.

“Photographs, which package the world, seem to invite packaging,” wrote Susan Sontag. She was talking about photographs printed in magazines and books, and exhibited on museum walls. This was before the advent of social media and especially Instagram, which is a different form of packaging, in which the person themselves – or the creator – is the commodity. This is how we are meant to read the aspirational travel photograph, because the person is the symbol, their lifestyle is the thing they are selling, and the place they are in becomes incidental to the lifestyle itself, filtered and distorted to fit into a 1x1 frame that matches their grid. The words beneath are important, because they tell us how they want to be seen, and so they tell us what to think. It is imperative that when reading the words and seeing the image, we think that this is aspirational, because otherwise, why would we buy it?

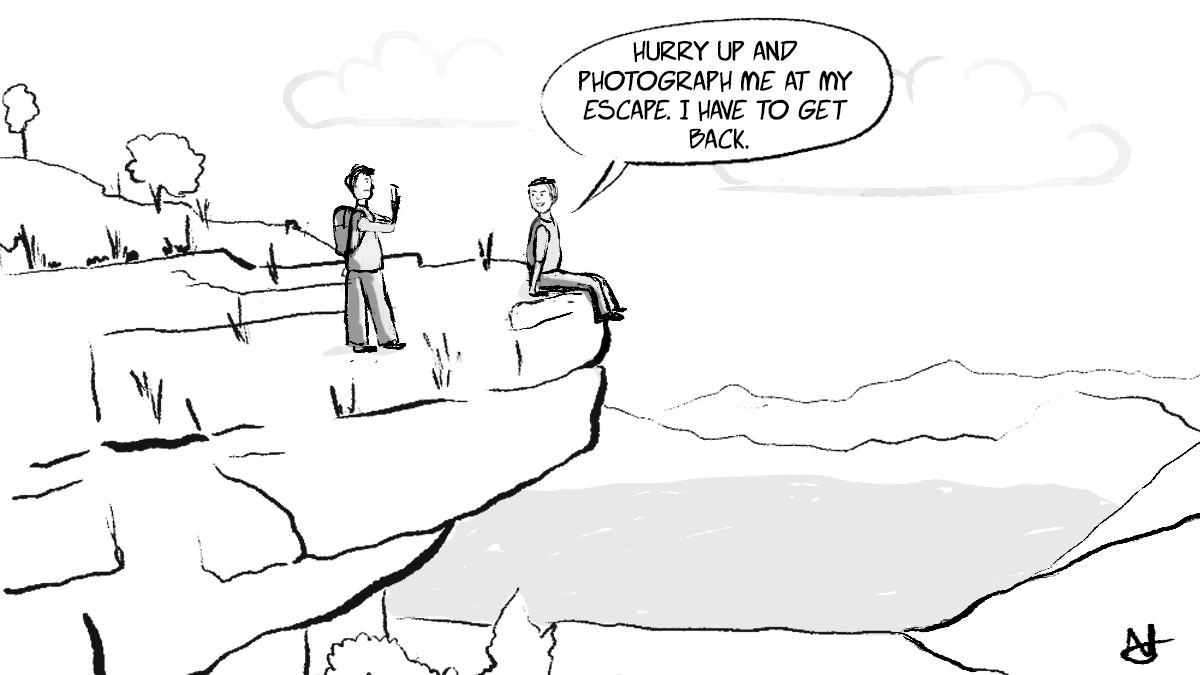

Ideas of escape

Travel is often sold as a way to escape a humdrum life, for a little while. That is why brief trips are labelled getaways. This appears to me to be a particularly modern invention: the idea that life is something that requires regular escape from. It would not be possible without air travel, because then getting to an escape would take too long to bear attempting. It is also influenced by the structure of the workweek: weekends are the time we have outside of work to contemplate escape, even though Monday inevitably comes around and with it, a return to routine. There is also paid time off: about two weeks a year in India or the USA, for slightly longer trips to “make memories” in, before returning to our cubicles. In some ways, life in corporate work structures became something that almost required occasional vacations, simply to make the rest of it more bearable. And yet, without those corporate jobs, we couldn’t afford the vacations, so perhaps that is the bargain we strike. For the remaining fifty weeks of the year, we have the images to keep us going, so it makes sense to make them as beautiful as possible. Memory is curious enough that at some point, the image of the experience becomes more real than the experience itself. We forget the long flight, the heat and the crowds, and only remember the photograph. But travel seems more a band-aid than a solution to the dreary sameness of a lot of jobs. If our regular life was filled with more novelty and interest, perhaps it would require less escaping from.

To travel is to live? No, to live is to live. And that life is made up of millions of everyday choices, one of which is to choose not to go on the trip, but to stay and wake up at the same time as usual, meet the same people as always, do the same work you did the previous day, cook the same food, water the same tree, pet the same dog, sleep in the same bed. Each of these little routines needs care and love to keep going, and they are not documented in photographs, but they are what Anthony Lane calls "the foolish, profound structures by which all of us … prop up our flimsy lives" There is value and beauty in them. After all, if all of us travelled, there would be nothing for the travellers to see. The structures they come to photograph themselves in front of, and the culture they come to experience were built by people who stayed put and did the work every day. And so, sometimes we don't go on the trip, but keep the home running, and keep doing the work we love, while waiting for the travellers to return with their photographs and tales.

If you liked this post and read upto here, do consider sharing it. It brings me more subscribers, which is something I want, though I’m not entirely sure yet why.

If you agree or vehemently disagree, leave me a comment and we’ll talk?

Loved this conclusion : "But travel seems more a band-aid than a solution to the dreary sameness of a lot of jobs. If our regular life was filled with more novelty and interest, perhaps it would require less escaping from."

I see a common trend in all those wide angled photos, they don't tell the story we need, they tell the story we crave. We want shots of escapism and viola we get them with the travelogues.

The idea of watching somebody else enjoying their life seems daunting to me. However sometimes it can also act as a motivation since it widens the perspective to take a break when work gets really hectic.

P.S. : I did laugh at Upamanyu's joke.

First things first, an extremely well-written piece and it certainly provides food for thought.

However, I'm not really convinced with the interpretation of a couple of historical references that were used. Let me try and explain why.

Ibn Battuta's reputation firmly rested on his ability to enchant audiences with narratives built around the distinctiveness of human behaviors and cultures. His keen eye for detail allowed him to recount experiences with a humanistic approach, which won him many admirers, including the Sultan of Morocco, who ordered him to narrate and document his experiences in the form of a travelogue, to a writer, who was equally fascinated by Ibn Battuta's travel episodes. Hence, The Rihla. There was a general interest among many to know more about his experiences as a traveler, so one can only imagine him being swarmed by people when walking the streets of Morocco.

The Grand Tour was largely an educational trip, which lasted for about 2-3 years. The prime focus was to explore and imbibe other European cultures. So, in many ways, it had a profound influence on the people who undertook it.

Now, both these references have a common thread. Both belong to eras where travelling for a longer duration and distance wasn't always feasible or viable for most. So, there was a genuine curiosity to know more about various cultures, people and their ways of life. Which now, in many ways, has been diluted by the internet.

Travel had a more broader meaning and significance in the past. So, my attempt has been to clearly distinguish between the purpose and idea of travel from the past and present.