We’ve reached the one year anniversary of the WHO declaring Covid-19 a global pandemic, and many on the internet are reminiscing about what they were thinking at this time last year. Except for the Chinese that is, who had their anniversary a couple of months ago, and tried to warn us early. If only we had listened. I know I didn’t. Around this time last year, I was sitting elbow-to-elbow at a table of 30 people in a small air-conditioned restaurant. I was offering everyone hand sanitizer and knocking elbows with people instead of shaking hands. We didn’t wear masks.

I recently read a piece by Helen Lewis, in which she writes that “a tennis ball covered in spikes” is the iconic image of the pandemic. I can think of others. Desperate eyes above masks, migrant workers trudging along endless roads in the heat of summer. Empty streets, full hospitals, showers of rose petals, massive protests. If I close my eyes, I can see these images like they are burned into my eyelids. Lewis is right, though, in wondering which of them will endure.

In his book “This Means This, That Means That,” Sean Hall says:

“One problem with it is that systems of communication themselves have an influence over—and can alter or augment—the way in which the world itself is viewed. In the field of semiotics, it is argued that the communication systems we devise actually frame, or dictate in some way, how we see the world. In other words, the world is not directly accessed through these various systems of communication; it is mediated through them. The systems themselves are apt to change what we think the world is really like, sometimes quite radically.”

Seen in that light, the visual communication on the virus has certainly mediated how we think of it.

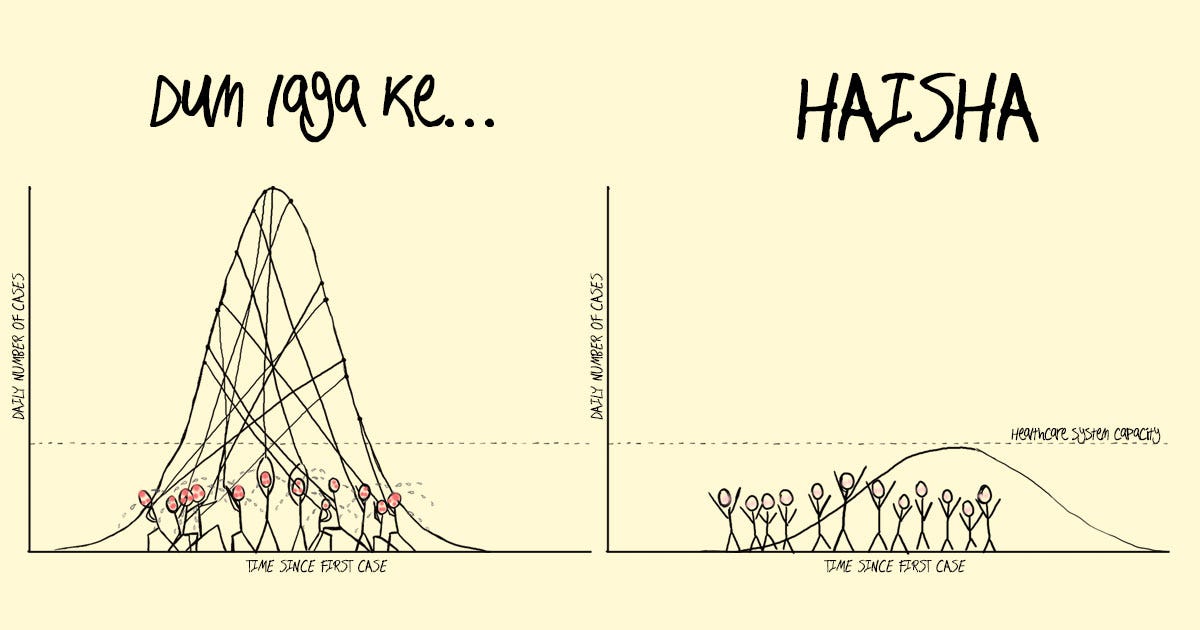

There were several different ways in which imagery changed in this pandemic year. Probably too many to cover in the span of a single newsletter, but I’m going to take a stab at it anyway. What we got accustomed to seeing as individuals, what government messaging looked like, and how public figures presented themselves, were all, I think, worthy of examination.

A collective grief

The early images of the pandemic were of the lockdown in Wuhan. The trailer of Ai Weiwei’s film “Coronation” captures the eerie desolation of Wuhan’s streets in those early days. It also shows health care workers in full PPE, and the sanitation of streets in the city. These images became commonplace last year, but they were very strange when we first saw them.

Afterwards, the images came thick and fast. Empty tourist sites, then overflowing hospitals, exhausted healthcare workers, socially distanced funerals, mass graves. In India, the lasting images were of weary migrant workers trudging back to their villages after the lockdown had stopped their work and earnings, and the trains to take them back stopped running.

In the UK, the Hold Still project documented this time using images submitted by people around the country.

In America, one lasting image was the field of white flags, an installation by Suzamme Firstenberg. Each flag represented one life lost. The sombre spectacle of it helped bring home the devastation this virus has wrought, and the loss it has left behind.

Individual memories

I’m going to be insufferable and link to my own tweet chain below, as an illustration of how quickly the way I was thinking about the virus changed. Early in March, I was anthropomorphizing it, for a piece that wondered how India’s health infrastructure and economy would withstand its onslaught. It became more ominous just a week later, glaring up at the Finance Minister as she walked a tightrope downwards arrow. A few weeks later, I was drawing it multiplying like rust, eating away at the chains of India’s lockdown.

One illustration that has stuck with me was Christoph Niemann’s “critical mass” New Yorker cover, in which he showed the spike proteins of the virus as dominoes, about to fall around a person who is sick. He described the moment as, “... the mood keeps changing drastically. No more jokes about touching your face or funny substitutes for handshakes. It’s like getting punched in slow motion. This is the moment just before the fist touches the chin.”

I can relate to that. I know my mood about the virus varied wildly, from it being something I ignored, to making daily charts about rising case numbers. I remember vividly, the dawning, slow-moving horror.

In some sense, the fear and grief we felt was universal in a way few things are. No matter where we were in the world, we were afraid of the same thing, at the same time. That manifested in work that we could all relate to.

I’ve also been looking at Economist covers as a visual documentation of this time, and how we have been thinking of the virus. The early images were only about China, before it expanded to become a global pandemic. My favourite one, though, is of the vaccine as the light at the end of a bend in a tunnel that is itself outlined with the shape of the virus. Fittingly, it is called, “Suddenly, hope”.

Government messaging

There was a lot of criticism of the changed message that came out in October, but the earlier and later messaging by the British government was rather excellent, I thought.

It laid out clearly what people were being asked to do. It used a yellow background with that caution tape border, that reinforced that this was a warning message. It called upon Britons to protect the hugely popular National Health Service. It was repeated consistently, most memorably on the podium from which the Prime Minister and others addressed the public.

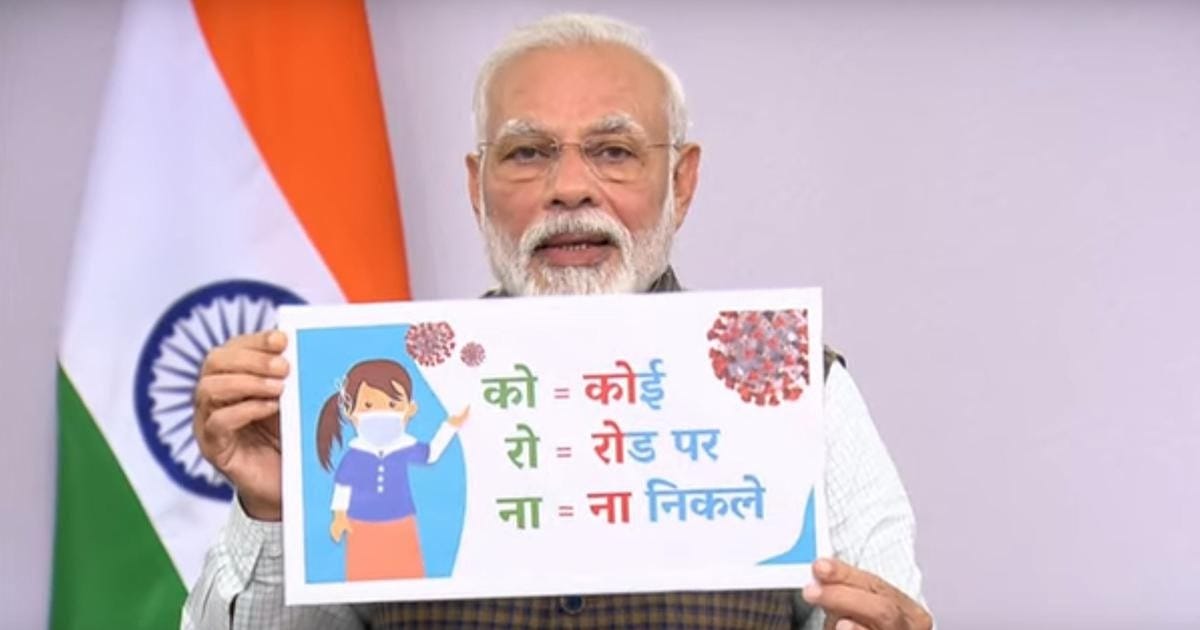

Compare that to the public messaging in India. The Prime Minister famously held up this sign:

Some of us cringed at the acronym, but it has the merit of really sticking in your mind. Of course, it was also tone deaf, given the thousands of migrant workers who were forced to go out on the road by the government’s lockdown.

Consider this poster put out by the Public Information Bureau. The design doesn’t guide the eye to a single message. In trying to give a lot of information, the designer ends up confusing the reader.

Other media fared better. What I thought was extremely smart was the phone message that was played every time you placed a call. It began with a person coughing and went on for a while, telling you what precautions to take. It was annoying, but effective.

There was also some truly entertaining visual messaging. The Delhi police had a man dressed up as Yamraj (the god of death) wearing a necklace of virus balloons. He was paraded along the streets of the city, along with a loudspeaker that repeated instructions for washing your hands and staying home.

There were also coronavirus helmets and statues visible at traffic crossings. These were, I would argue, less effective, because while they conveyed that the virus was a threat, they didn’t really tell you what you could do about it.

What a lot of the messaging didn’t capture was the uncertainty of scientific advice. The WHO changed its stance on masking and how the virus was spread. The messaging didn’t quite keep up, with instructions to wash your hands persisting till long after we knew the virus was airborne. Such confusing messaging can also be seen about vaccination, with vaccine safety and efficacy being debated in a way they never used to be before. I don’t have a solution for this, but I do think visual messaging needs better ways of capturing uncertainty and complexity, because otherwise it becomes untrustworthy.

Public figures

The Indian Prime Minister was an early mask-wearer, and characteristically, he used the occasion to signal his pan-Indian brand. This manifested in the gamchas (scarves) he wore on various television appearances, ranging from the south Indian angavastram to an Assamese gamosa. It was smart and effective, both in reminding citizens to wear masks, and in reinforcing his own brand.

A particularly egregious example of a public figure’s messaging was Donald Trump, who made a very big deal of not wearing a mask. Indeed, even when he had the disease and was visibly straining to breathe, he whipped off his mask for a photo-op.

In this, he imitated Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, who also took off his mask in a TV appearance while he had the virus.

Trump’s successor, Joe Biden has been extremely consistent with wearing his black face mask, deliberately removing it before giving a speech, and wearing it again afterwards. Such consistency is important, because it cements the idea of wearing masks in people’s minds.

What will we remember?

What will the world look like in a few years? I suspect, remarkably like the world before. We are very quick to forget, to move on. The loss was collective, but for us lucky ones, not personal. We will remember 2020 as “a strange year” and tell stories about it, but that will likely be it. The status quo is powerful, and it wants to return. Will we let it?

The world has been changed. The old order only worked for some, but those some are powerful and they want the world back the way it was. For the rest of us, this is a chance: a slim one that narrows further every day. But we need to grab it in every way we can. How to remember, when everything is telling us to forget?

One way to do this is to bear witness. We document what we are going through in the mad hope that someone, someday, will read what we wrote, look at the images we made, and heed our sadness and desperation. That they will listen, and not repeat our mistakes. That they will be better than we were.

I apologise for disappearing for all these weeks. I’ve been working in a few different media, making illustrations and data graphics. I notice that when I spend time drawing, writing of any sort gets harder. My mind begins to think in colour, line and form, and the words slip away. So I put off writing till I was done with colour. I’ll try to warn you when I disappear next, or share what it is I’m working on, instead of a written newsletter.

If you liked this newsletter, do tell someone about it? This is how people get to know about it and me, and in this strange world we inhabit, name recognition is a kind of currency. It – convolutedly – pays my bills, which in turn keeps me producing more newsletters.

The button to share is right here: