What's with all the flower crowns?

A fortnightly newsletter that breaks down the visual construction of imagery.

I don’t know what the world will look like when you’re reading this. When the 2016 US election took place, I was in design school. I had woken up in my hostel room at 5 am, and was following the results on the New York Times homepage. I thought I’d be celebrating the win of the first female President of the United States. I had admired Hillary Clinton for a long time, and I wanted to watch her win, so I could tell my children about it one day. Instead, I watched the needle shift inexorably towards Trump. It was a grim certainty by 10 am, which is when I had a meeting with a professor to discuss an animation I was working on. My professor didn’t know yet that Trump had won, so when he asked me how I was doing, I told him. After that, we sat in silence for a few minutes. Then he turned to my work and said, “What’s the point of this anymore?”

I hope this Thursday morning is different. I am writing this on Tuesday, after reading that storefronts in New York are boarding up in preparation for civil unrest. I hope there is peace. We need democracy to succeed. It’s a deeply flawed system, but it’s the only workable one we have. I wish we could elect leaders who believed in it.

For now, flower crowns.

There is a certain section of the internet that exists in my periphery, and it consists almost exclusively of women having babies. Those algorithms know my biological clock better than I do. Pregnancy announcements, gender reveals, baby photoshoots, all result in a steady stream of content. The images are carefully staged, lit, and shot. I pause to look at them when they pop up in my social media feeds, because they are often very lovely. In recent years, I’ve been noticing a particular kind of image. It is usually shot in early morning or late evening light, and the subject is a woman who is wearing a floaty pastel gown while cupping her distended belly. She is looking away from the camera or down at her belly, and whatever she sees is making her pensive. More often than not, she is wearing a flower crown.

To be fair, there are plenty of images of women who are not pregnant also wearing flower crowns, usually while frolicking in nature, in similarly ethereal light, with vaguely broody expressions.

This sort of image is not one I associate with Indian women, pregnant or otherwise. Indian women wear flowers of course, but usually as gajras rather than crowns. I get the association with fertility, but my own immediate association with flower crowns is – somewhat unjustly – Madeline Bassett.

I don't want to wrong anybody, so I won't go so far as to say that she actually wrote poetry, but her conversation, to my mind, was of a nature calculated to excite the liveliest suspicions. Well, I mean to say, when a girl suddenly asks you out of a blue sky if you don't sometimes feel that the stars are God's daisy-chain, you begin to think a bit.

-P G Wodehouse, “Right Ho, Jeeves”

My research didn’t throw up any actual instances of Madeline Bassett wearing a flower crown, but it isn’t much of a stretch that she would, considering her fondness for daisy chains.

The association of a certain type of white woman in an imagined pastoral setting goes a lot further back than the Bassett. For those of us who grew up in erstwhile colonies, consuming English culture, it dates back to Merry Olde Englande: an imagined time of idealised agrarian existence, before the Industrial Revolution and colonialism.

There’s also a related set of women, characterised by languor and mental fragility: the delicate Ophelias, created by men and destroyed by them. Madeline Bassett seems to me to combine both tropes, for laughs.

The flower crown pops up in many European cultures. Laurel wreaths date back to ancient Greece, although their origin myth is quite disturbing. Daphne, a nymph, turned herself into a laurel tree to avoid the advances of Apollo, the son of Zeus and the Greek God of poetry. Apollo used his powers to make the laurel tree evergreen, and its leaves have been used ever since as a symbol representing and honouring him.

In Rome, Flora, a goddess of flowers and spring and also of fertility, was represented wearing a crown of flowers and leaves.

Modern interpretations

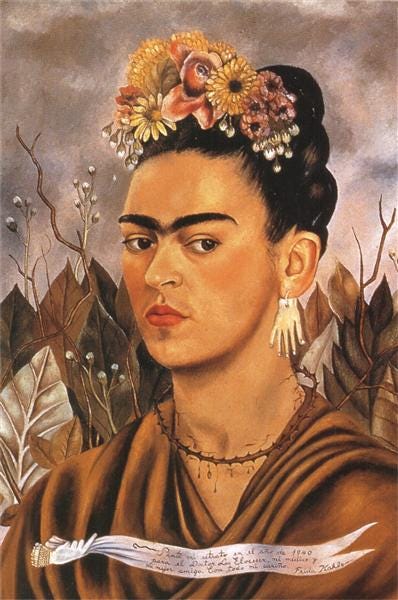

It is in the art of Frida Kahlo that the flower crown starts to get really interesting. She painted 55 self-portraits, and in several of them, she wears flower crowns as a nod to her Mexican heritage. Unable to bear children, and having suffered three miscarriages in her brief life, she would paint flowers as symbols of fertility in bright, contrasting colours, while showing thorns that pricked her and drew blood. Her gaze in these images is direct and challenging. “I paint flowers so they will not die,” she said.

It occurs to me that there is a great deal of difference between art in which men represent women, and art in which women represent themselves. What then, to make of the images that pervade my Instagram feed today? These women are either the creators of their own images or are willing participants. They choose to represent themselves in this way, selecting the setting, the symbols, and the expression. Why do the images they make have more in common with Ophelia than with Frida?

I think John Berger got at the heart of the matter when he wrote:

Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object - and most particularly an object of vision : a sight.

I know I do this: I watch myself the way I know I am being watched. I judge myself with all the judgement I know those glances have. And because men have a great deal more power in this world, I have been conditioned to defer to male judgement, and to present myself in ways that are acceptable and appealing to men. And this brings me, as all things on the internet eventually do, to Beyonce.

In Lemonade, her groundbreaking visual album that linked her pain of being betrayed by her husband with the pain of generations of Black women and their struggle, Beyonce recites: “I tried to change / Closed my mouth more / Tried to be soft, prettier / Less... awake”

She doesn’t bother for very long in the album. Quite soon, she’s smashing cars with a baseball bat. It looks very freeing, to stop caring for the approval of men.

Free love, and capitalism

There is one other aspect to this that is possibly even more powerful than the male gaze, though of course it is influenced by it. Take The Summer of Love: catalysed by the Human Be-In rally in San Francisco, 1967. It was a coming together of artists, writers, and poets, espousing communal living, environmental awareness, and a rejection of war and consumerism. They embraced cheap foreign travel as a means of understanding culture and communication, and drugs as a form of escapism.

The idea of “Make Love, Not War” is dulled now, by decades of cynicism and appropriation, but I can imagine it being revolutionary back then. A prominent symbol of the time was the flower crown. The flowers stood for peace and free love. Men wore them too, even as they refused the draft and protested for peace. The movement fizzled out quite rapidly, plagued by drug addiction and homelessness, but also backlash by the establishment. Some vestiges survived: for instance, I still meet plenty of backpacking Americans trying to “find themselves” in Bombay.

Much of the counterculture has since been successfully portrayed as distasteful and fringe, but the imagery remains. Its potency has been diluted by, what else? Capitalism. Now, on Etsy, I can find more than 7,000 options for hippie flower crowns, modelled unironically by pretty white women, often gazing away from the camera, pensively. There are also flower crowns for babies (girls, of course. They must be gendered from infancy) and even sometimes, dogs. There are several hundred Instagram filters with flower crowns, many of which also helpfully whiten your skin.

Humble wildflowers are replaced by hothouse roses. Unwashed hair – sometimes because people were protesting in public for weeks on end – is replaced by beachy waves. Men don’t wear flower crowns anymore. The Summer of Love itself has been appropriated into music festivals. Celebrities dress like hippies for Coachella now, and the trend trickles down through the fashion economy as the must-have look for the summer.

And thus are symbols deprived of their power.

The thing about symbols is, their interpretations change constantly, just like words. We appropriate and use them, sometimes with thoughtfulness, sometimes without. They are very hard to pin down to one meaning, but instead carry within them echoes of all they have represented before, and all that comes after.

Flowers and power

In 2018, Beyonce was the first Black woman to ever headline Coachella. At the time she said, “When I decided to do Coachella, instead of me pulling out my flower crown, it was more important that I brought our culture to Coachella.”

When she emerged on that stage, she didn’t wear a flower crown. She wore a Nefertiti headdress.

But she was on the cover of Vogue in the September issue that year, wearing a coronet of flowers, and an Ophelia-like dress, gazing directly at the camera, bathed in golden light that made her skin look like honey.

The headdress was designed by florist and milliner Phil John Perry, who was interviewed about it. He said, “I personally want to get away from flowers being pretty. It still has to be gorgeous and beautiful, but it doesn’t have to be soft for a woman to wear.”

What I’ve been reading

I thought it would be nice to do a roundup of links, so here goes:

When researching this piece I came across this hilarious and charming piece of reportage by Mridula Chari.

How Indian brands are finally having to reckon with hate.

The Economist nailed their cover design.

Estonain label Marit Ilison creates some truly beautiful coats.

When creation is fueled by private nationalism and not public desire.

Thank you for reading this far. If you have any comments, suggestions for future topics, or just want to say hi, you can leave me a comment or email me at nithya@nithyasubramanian.com. I’d love to hear from you.

If you like this sort of thing and want it to show up in your inbox, here’s the Subscribe button.

I leave you with this message:

Edited to add: An earlier version of the newsletter had an image of the baby without the flower crown on, by accident. Sorry, subscribers.