Show and Tell: What is up with the Prime Minister’s beard?

A fortnightly newsletter that breaks down the visual construction of imagery.

Narendra Modi turned 70 in September. With age comes the appearance of wisdom. As is the Prime Minister’s wont, the appearance of wisdom manifests in a doggedly literal fashion.

Source: YouTube

It is possible that Modi – like the rest of us – is avoiding going to the hairdresser’s. But that seems unlikely, given how image-conscious he generally is. None of his colleagues, besides, have made such changes to their appearance. There is something deeper afoot.

What is it about a beard?

Consider this poem:

Be or Busy

My Deepest song

has not been sung yet.

Still in wait for din to settle

and Silence to blossom.

When I sing that Song

will you Be. Or Busy.

It’s execrable stuff, right? The complete lack of any sort of rhyme or metre or grammar, the random capitalisation, the confusion of its ideas. It’s the sort of thing you’d expect as a contribution to the school magazine by a 9th standard boy whose parents don’t believe in being critical. He wrote it in “a fit of inspiration” and will read it out to you if you aren’t careful.

Now consider it in this context:

Doesn’t it suddenly seem… profound?

I posit that this is the power of the beard. Also the robes, and the personality, but mostly the beard. It has a strong association in our minds with wisdom. A clean-shaven Sadhguru just doesn’t have the same effect.

My reading is certainly simplistic. The Sadhguru is another diligently constructed public persona: a saint who rides bikes and talks to young people in slickly produced videos. He speaks in careful banalities. He is also adept at translating spiritual mumbo jumbo into corporate jargon, which is something of a tautology.

At some point I might do a deep dive into the image-making of godmen, but that is the stuff of a later newsletter.

For now, let’s return to beards. They have a long history.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore, a Professor of History at Wright State University, wrote of the history of facial hair in his book “Of Beards and Men”. It is written largely from a Western perspective, and traces the many formulations and reformulations of the beard, and thence, ideas of manhood themselves. Not all these ideas apply to the Indian context, but some certainly seem to. Consider the persistent linking of beards to virility.

In Oldstone-Moore’s telling:

Aristotle ... agreed that hot fluids, including semen, were the ultimate source of hair, and that this explained why men had more hair as well as more strength and reasoning power. Men with “strong sexual passions” had especially full, thick beards because of an abundance of semen, but these men were also more likely to go bald from the depletion of that semen through repeated intercourse. More sex, more hair loss.

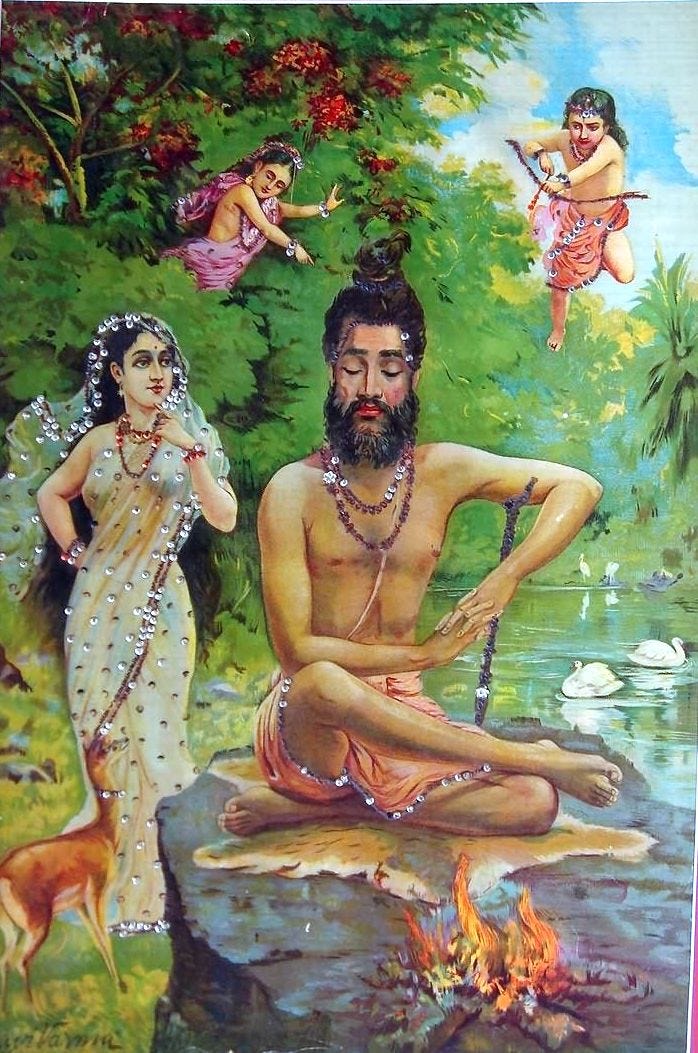

Specious as Aristotle’s logic is, the association with virility endures. There is a reason why celibate monks shave their heads and faces. Many sages in Indian mythology, on the other hand, are shown as having long, flowing beards. They also instruct young princes in the art of warfare, have notoriously bad tempers, and are not above being seduced.

Vishvamitra Tapobhang, from the Ravi Varma Studio. Wikimedia Commons

In such a connotation, the beard could well be seen as an extrapolation of Modi’s famous 56 inch chest.

Why would Modi grow his beard out now?

Politicians and public figures have long used their appearance as a form of signaling. Consider Nehru’s cap and bandhgalas, Gandhi’s mendicant style, or more recently, Mamata Banerjee’s unkempt hair or Rahul Gandhi’s studied dishevelment. In the US, Trump signals his Trumpiness with long red ties and MAGA hats, while Biden wears cool-guy aviators and Harris wears sorority pearls. For each of these public figures, the image is a shorthand for their personality, and it helps with their branding to be consistent with it. Narendra Modi’s branding abilities are nothing short of masterful.

The Prime Minister does not conduct press conferences, and is very selective about interviews. His speeches are scripted and carefully controlled, as is what he says in his “Mann ki Baat” programme. Thus, his primary mode of communication with the media and the public in general, becomes visual. This is why the headdresses, the scarves, the robes and the woven suits, all take on so much more meaning. He really does show, even as he steadfastly refuses to tell.

He has flirted with the rishi symbolism in the past, most memorably right after voting in the 2019 elections ended, when he went to the Rudra cave in Kedarnath to meditate. There have also been hints in his enthusiastic embrace of yoga and the frequent images of him performing it. Through all those though, the facial hair remained consistent.

The beard, coming as it does now, appears to signal a shift: from the technocrat Modi who was pro-business and wore tailored navy suits, to the atmanirbharta Modi who wears handwoven angavastrams and cotton kurtas.

Why do we fall for this?

“A sign is quite simply a thing – whether object, word, or picture – which has a particular meaning to a person or group of people. It is neither the thing nor the meaning alone, but the two together. The sign consists of the Signifier, the material object, and the Signified, which is its meaning. These are only divided for analytical purposes: in practice a sign is always thing-plus-meaning.” - Judith Williamson, “Decoding Advertisements”

We, as Indians, have been trained to respond to beards in a certain way. The immediate association for the majority is with a rishi or muni, the sort created in Ravi Varma-inspired calendars, the Ramayana TV series, and Chyawanprash ads. Consider this vintage Dabur Chyawanprash ad:

We have been conditioned to make this association. To apply Williamson’s deconstruction, the Signifier here is the beard, but the Signified is that particular mixture of wisdom and vigour, sacrifice and virility. By growing the beard, Modi transforms himself into the thing-plus-meaning.

This association is specific to where we live. In much of the West, the association would probably be to Father Christmas. In the Middle East, it may well be to religious clerics.

Such an association is cultural, and already ingrained. So when Modi grows a beard, he is attaching himself to the imagery and stories that exist. As he repeats the appearance consistently, the associations get cemented.

There is the slight chance that he might also be associated with a Sufi or an imam, but he precludes that with the preponderance of saffron in his clothing and the rhetoric of his followers.

Show and Tell is a newsletter that breaks down the visual construction of imagery. It comes out every fortnight.

If you like it, do subscribe, so it can show up in your inbox? Tell your friends about it?

The first few editions will be free, but I will be converting this to a paid model quite soon, with only the occasional free newsletter. Subscribers get additional perks and discounts on merch, so stay tuned.

If you have comments, criticisms, ideas for a future newsletter, or anything else you’d like to talk about, do write to me at nithya@nithyasubramanian.com

Very well broken down and analysed. Thank you for introducing such a newsletter, especially at this time of ceaseless visual consumption, understanding semiotics plays such an important role.

Very important topic contemporarily. I like the structure and the length of this newsletter. I do think there was more to be elaborated on the " Why now front ". Particularly the pandemic angle. How the beard subsconsciously signals wisdom and a guiding light given the current times. There's also some things about visual charisma and leadership, which you have talked about but maybe just different semantics. Looking forward to more stuff. Kudos!!!